Complex housing issues in our communities

Pimatisiwin provides shelter to unhoused Edmontonians, but lack of communication and security measures bring concerns to Elmwood Park

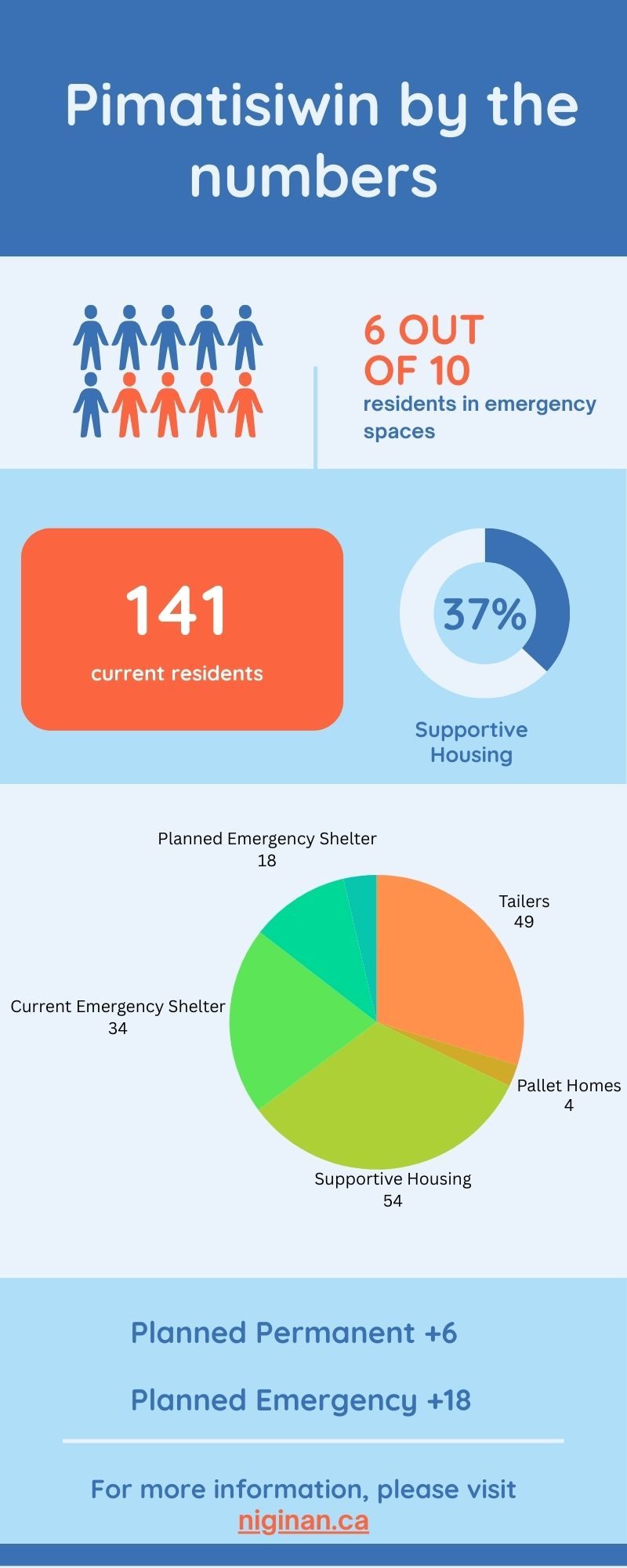

In 2021, NiGiNan Housing Ventures was given $5 million by the City of Edmonton and $5.7 million from the federal government’s Rapid Housing Initiative to develop the former Sands Hotel into 53 units of supportive housing. The site was named Pimatisiwin (translation: life).

Since November 2021, the site provided temporary shelter and supported COVID-19 physical distancing needs at the time for 105 unhoused Edmontonians. In early 2022, NiGiNan began renovations to transition the hotel to supportive housing. Initial plans were to have the project completed by the end of the year, but the opening date was moved to 2023 due to undetected asbestos contamination. The project seemed to be complete according to plan. But in December 2023, the Elmwood Park community felt blindsided when two large CIVEO trailers and four small structures appeared in the parking lot of Pimatisiwin late one night.

There had been no notice or discussion shared with the community that additional spaces would be added.

“If you want to maintain a good relationship with people, come to us at the beginning [of a project],” says Morgan Wolf, Chair of the Elmwood Park Community League. She sums up the community’s feelings that the way it was handled “does not give you trust with people. You have to be transparent.”

A Tense Meeting

In 2021, the community met with NiGiNan Housing Ventures regarding the plan to build Pimatisiwin as supportive housing to help individuals exit homelessness. The consultation made the community feel their concerns were heard. They knew the renovations were near complete and were prepared to welcome their new neighbours.

The overnight appearance of trailers two years later surprised residents.

On January 16, 2024, in an effort to resolve the concerns regarding the trailers, over 40 Elmwood community members (from a community of fewer than 1,200) met with administrative representatives from the City of Edmonton and Métis Ward Councillor Ashley Salvador, Métis Ward Councillor; Edmonton Police Services (EPS); Keri Cardinal-Shulte, CEO for NiGiNan housing; Cala Hills, site manager at Pimatisiwin; Janis Irwin, Edmonton-Highlands-Norwood MLA; and Blake Desjarlais, Edmonton Griesbach MP.

Missing was representation from the Government of Alberta Ministry of Seniors, Community and Social Services.

The atmosphere in the hall was tense. The community correlated the rise in disorder to the presence of the shelter. One woman stated that drug dealers regularly meet on the corner of her property and she sees a lot of used drug paraphernalia. “We understood it would be recovery; we did not know it would be a shelter,” followed Virginia Gardner. The community had additional concerns articulated by Gardner. “I totally agree with what you are doing, but I disagree with harm reduction.”

The number of unhoused individuals in Edmonton has doubled in four years due to the COVID-19 pandemic, static social support from the provincial government, lack of public housing, and a recession. With no stability or access to help with food, limited clothing and shelter, and virtually non-existent mental health support, many people without homes resort to theft to shelter themselves and are often mired in mental health or addiction crisis.

The effects of these events spill over to housed people: overdoses, needles in the park, attacks, and theft, from toys and bikes to tires off cars. Bob Acker shared how he called 911 to report an attempted break-in at 2 am only to be told that kicking at a door in the middle of the night is not a crime. Acker asked, “What does it take to get a police response?”

At the meeting, EPS, Neighbourhood Empowerment Team (N.E.T.) representatives, and Park Rangers (responsible for encampments) listed the ways the community can reach out for help: calling 211, 311, or 911, or documenting a complaint with the EPS non-emergency line. One community member, who is home during the day, responded. “You keep telling us to document and call you. I could spend all day doing this. It feels like it's my full-time job. I feel traumatized from witnessing all this [disorder]. Why is it my job to get you to keep our streets safe?” Her comments were greeted with applause.

Steve Larson said he has begun patrolling Elmwood Park twice a day, bringing bottled water and snacks to people unable to get into the shelter before asking them to dismantle their tents. The Elmwood Park resident has become someone the community calls when they have concerns. He stated that he “appreciates the reaction time” from NiGiNan and says that when he calls Cala Hills, “she deals with it.”

Despite his good relationship with NiGiNan, Larsonsaid the presence of the shelter attracts “bad guys” travelling along 75 Street north to south. “That’s where the crime is,” he added. He requested that EPS drive through the community when they’re around the 82 Street corridor. EPS representatives agreed to increase their presence in the community.

Confusion and Mistrust

Much of the frustration and mistrust regarding the shelter came from a surprisingly quick bureaucratic decision and two layers of government with their own communication issues.

In a follow-up interview, Cardinal-Schulte points out that NiGiNan staff deal with city and provincial administration, not elected officials. City administration — both the city housing department and the city permitting department — have no say as to whether or not a project will proceed. Projects only happen if the province provides funding through the Homeless Supports and Housing Stability Department (HSHS), Ministry of Community and Social Services. Elected officials (City Council) are often not advised of the outcome of a project until both the plans and permitting (administration) and the provincial funding are both in place.

According to Cardinal-Shulte, the city housing department had approached NiGiNan to ask if they would partner to trial four Pallet homes for the Cold Weather Shelter Pilot. Pallet, an Oregon-based Public Benefit Corporation that builds emergency shelters, wanted to test their product in a Canadian winter.

City council meeting minutes from April 17, 2023, show that Administration was asked to provide a report regarding Indigenous-led shelter and transitional spaces. The Cold Weather Shelter Pilot report was presented to Council in December 2023, with a design plan expected by January 2024.

In the meantime, NiGiNan applied to the province (HSHS) for operational funding for their ongoing emergency shelter in the Tavern at the beginning of November 2023. They added the Pallet homes to their application. HSHS advised that they fund a minimum of 50 temporary emergency spaces and required the application to include additional spaces. To prepare for winter if their funding application was approved, NiGiNan also submitted a development permit to the city to “move on 3 temporary buildings (dormitory, dining Car and Pallet Homes (4 of) for a Supportive Housing Use (53-person capacity).” At that point, they did not know what funding they would receive from the province.

At the end of November, NiGiNan found out they received money from the province for the project. Then they had two days' notice that the trailers would be arriving from British Columbia. These tight turnaround times meant that community members were not informed about the 2023/24 emergency shelter project, with the exception of a notice to the nearest neighbour within 60 metres who fell under development bylaw).

When asked about the funding for the trailers at the January 16 meeting, Councillor Salvador stated, “I am not sure what went into making that decision but I am disappointed that a provincial representative is not here to speak to it.”

Coexistence

The appearance of the trailers on the heels of negative interactions with unhoused individuals exacerbated Elmwood Park’s frustration.

Initially, the community had requested a fence to separate Pimatisiwin from the playground across the back alley. At the January meeting, a community member pointed out that there is a hole in the fence along NiGiNan property and stated that drugs were being sold to Pimatisiwin residents through the fence. The community member also stated that people use a two-by-four to jump over the fence. Cardinal-Shulte responded that trying to meet the competing needs of the community is difficult. “We put in the fence at the community request, but then we get complaints from people stating ‘that is where we walk,’” she said.

Cardinal-Shulte also noted that the privacy screen on the fence had still not been installed, and that she needed to follow up with the fencing company.

Morgan Wolf presented two requests on behalf of the Elmwood Park community at the meeting: First, community members want a dedicated number to call when they have issues with people using or attempting to use the shelter. Second, they wish to have security patrol the area. NiGiNan reiterated that community members can email anytime or pass on concerns through Wolf or Steve Larson.

Wolf said that the community wants to have good relations with people. She reiterated that Elmwood Park Community League would like NiGiNan residents and staff to attend their events.

Cardinal-Shulte said she understands the frustration with people who are acting inappropriately and creating problems. “The damage which has happened over 200 years cannot be undone in 30 days,” she stated. “We meet people where they are at.”

When asked about how she would respond to questions from the community, Cardinal-Shulte said she is always available, because she feels so strongly about what NiGiNan does. She concluded by saying, “I am committed to doing the best we can with what we have.” At the meeting, she also invited community members to arrange a visit to Pimatisiwin any time they wanted.

“I want people to have safe and loving housing,” said Cardinal-Shulte. “NiGiNan’s job is to find solutions for Indigenous people. We do whatever we can to get people off the street.”

Elmwood Park resident Andrew Altimas is uniquely positioned to articulate the complexity of the situation. He has lived experience of former homelessness and recently witnessed his roommate being assaulted by five people. “If one person is suffering, we are all suffering,” he states. “We cannot separate ourselves from it. We all have to have healing.” Above all, Altimas has hope for the community.

“If we all work together, we can find a unique solution for Edmonton.”

Rebecca has attended free concerts as a bouncer, juggled plates as a waitress, completed a degree in microbiology, laboured in the oilfield cleaning storage tanks, and worked as an editor for the Government of Alberta. In her current incarnation, she has been a full-time photographer for the last 15 years, is exploring writing and co-parents four nearly-grown children.